Originally printed in the Washington Post Magazine, Education Issue, April 11, 2013

It feels like a lifetime ago, but it was New Year’s Eve morning, a few short winter months back. The house was quiet. At 2:20 a.m. our three boys —18-year-old twins and a 21-year-old — had finally finished a whirlwind of applications to 18 colleges and collapsed into bed.

The best-laid plans of parents and guidance counselors are of no avail against the forces of young-adult procrastination. All December, our house had reverberated with curses at a temperamental Internet and voices yelling: Can someone read this essay and tell me if it sucks? What on earth’s an SSN? Hey, what’s the difference between race and ethnicity? What’s my stupid password? Desperate e-mails flew to mentors begging, Please, please send that letter of recommendation before tomorrow’s deadline! Name-calling escalated between the twins as one got called for an interview while the other had to request his. Doors slammed. Dinners became moody eggshell walks. And secretly, we-the-parents feared a shutout.

They could all be living at home next year, watching reruns of “Family Guy” and glaring at us from the sofa.

Most of their submissions had involved clicking the Common Application’s “send” button, but while the boys slept that last morning, we-the-parents dashed to the post office to mail ancillary material, in our case, music audition CDs, by the Jan. 1 deadline.

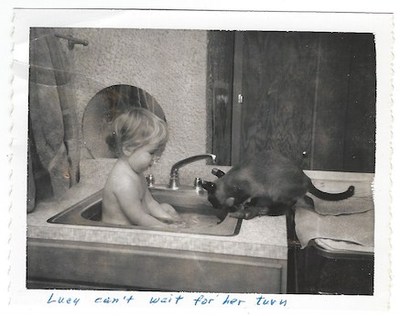

After that frenzy, two dogs snoozed in the corner (the third had stolen back into bed with one of the boys), unaware that all the angst-ridden behavior of the last weeks would deprive them of all three of their favorite playmates before long.

We-the-parents stared at each other over mugs of scalding coffee. So, what now?

Thousands of families had doubtless made the same post office dash. Thousands of other kids had doubtless left it to the last millisecond, too. And most were applying to colleges buried in applications. Schools could populate their freshman classes several times over with excellent incarnations. It’s like mass insanity.

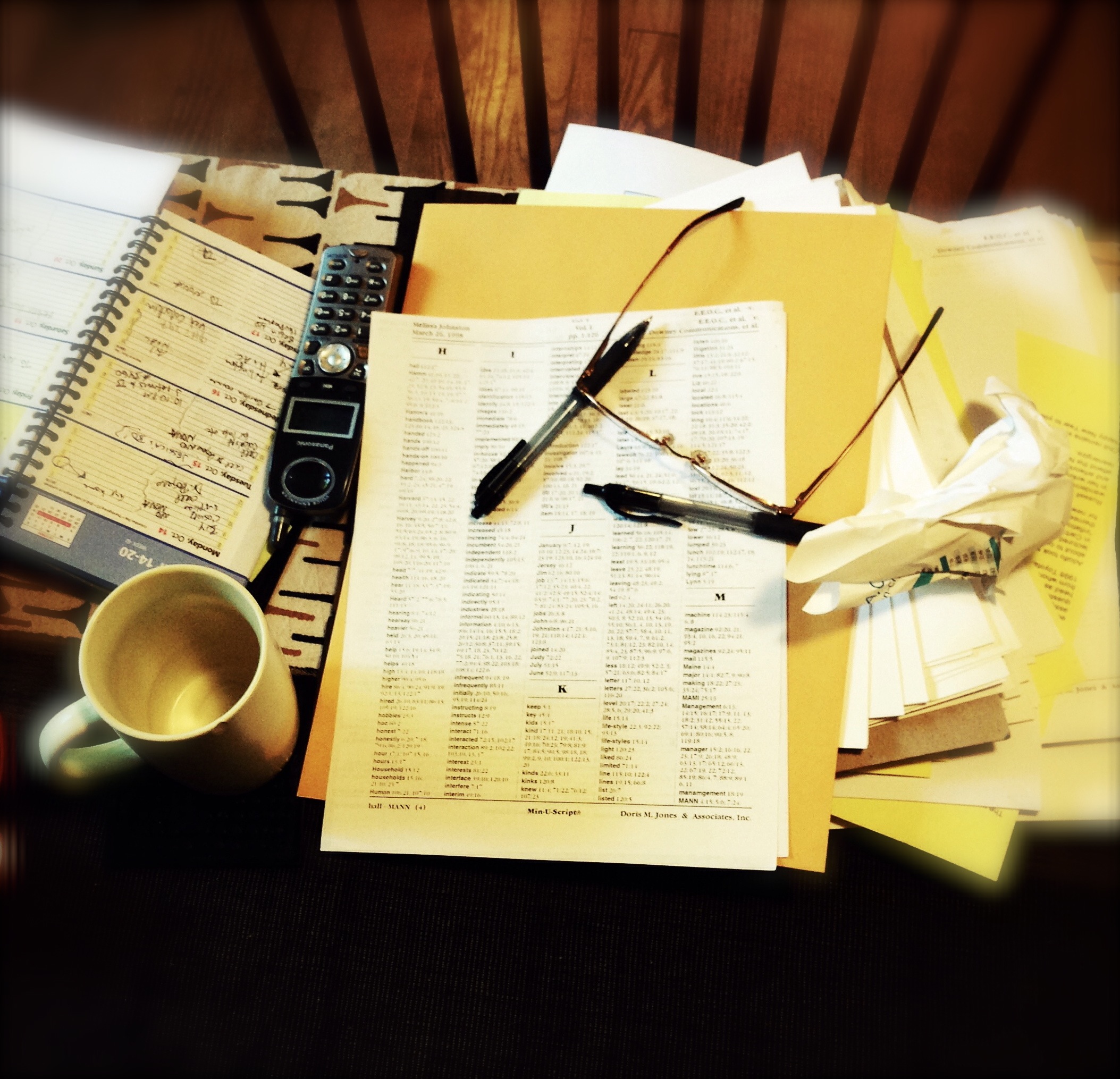

So, what now? Weren’t we all thinking it? After the wordsmithing, the second-guessing and the fee-paying — we shelled out $970 in application fees, $618 to the College Board for SAT fees and its financial aid form, and I don’t even want to think about the test prep expenses — what happens? Who goes through the applications? How much time do they dedicate to each one?

Rumors abound among high school students. I remember our eldest saying, with a feeble laugh: “Did you know that admissions officers use headless chickens who run around, then fall and bleed on a pile of applications? The ones with the most bloodstains get accepted.” I’ve overheard the false bravado of the twins and their friends: “Ouija boards and Magic 8 Balls, dude. They probably play pin-the-tail-on-the-application while laughing hysterically.”

It would be eye-opening, wouldn’t it, to take a peek behind the wizard’s curtain? I wondered if any schools would be willing to reveal the most naked workings of their famously opaque admissions processes and allow us to have a look. I decided to approach schools in the Washington area. The first school slammed the gates, but Goucher College, Howard University and the University of Maryland welcomed a full view from start to finish, and the University of Virginia agreed to phone interviews.

Goucher College

Goucher College is a small, private liberal arts college tidily nestled in 287 wooded acres in suburban Baltimore. It is the only college in the United States to require its students to study abroad. President Sandy Ungar, sipping tea in his office overlooking winter-bare trees, is sympathetic to beleaguered applicants and colleges alike.

“It’s such a tense time. There’s almost no way for everybody to be wise about it. This confluence of forces — anybody who ends up making a wise decision is really lucky,” he says.

Before his tenure, Ungar had various careers, including a stint as a Washington Post staff writer in the early 1970s. He is a trim, energetic man with an engaging manner. “I’m very interested personally in the kids who are searching and who’ve learned some humility along the way, who know how to learn and who know that there’s still so much to learn, and who are not fooled into thinking that taking 12 [advanced-placement classes] makes them brilliant.”

The conference room where the admissions committee is meeting has the air of a room temporarily cleared for utilitarian purposes. Chairs are stacked against the walls, and two large tables are shoved together, their surfaces crawling with cables and modems that lead like life-support lines to the laptops of four admissions officers. These officers are Lisa Hill, Nenelwa Tomi, Will Lederer and Director of Admissions Corky Surbeck, joined later by Kim Murdock. Tomi, Lederer and Murdock are Goucher alums. Seven admissions officers total rotate in and out of the committee meetings. When not present, chances are they’re cloistered in their offices reading; “reading,” in the language of admissions, means examining application files.

The room is dimly lighted, as an enormous spreadsheet is projected on a wall. It represents the 3,500 applicants for the fall term — 500 applications per first-read counselor, although each file gets a second review by another counselor. The applications review, or reading period, takes about 13 weeks from December to early March.

Prospective students are listed alphabetically by high school. Across the top of the spreadsheet are more than 20 fields, such as region, grade-point average, midyear GPA, class rank (if available), ethnicity, whether the student is of athletic interest, whether he or she took the SAT (optional at Goucher) and the student’s contact history with the college. This constitutes the student’s personal row.

For academics, Goucher uses a 1 to 6 ranking system based on standardized test scores and students’ recalculated GPA (many colleges adjust high school GPAs to level the playing field between schools of varying strength and number of honors or AP classes offered). An A to D rating reflects all non-academic components. “An A represents a student who is multi-dimensional with broad leadership experience,” Surbeck says, “while a D represents a student with little extracurricular activity.” Goucher is considered selective, accepting 73.5 percent of its applicants.

At most schools, students discussed in committee are under review because their cases are not clear-cut. Michael J. O’Leary, Goucher’s vice president for enrollment management, explains: “What one person might see as a red flag, the other person might see as someone who has overcome an obstacle and has learned from it and will flourish.”

At Goucher (and many other schools), the officer who presents the case is familiar with the student’s high school and all the schools in its region. The officer also knows the school counselors, which is useful if he or she needs clarification or information. High school counselors are an essential piece in this process. In some cases, they are the most valuable link between student and college.

In one discussion, a student’s GPA declined in her junior year to below 2.8, the floor of what Goucher generally accepts. All the officers look at her files on their laptops, searching the data to get a sense of the person behind the numbers. Surbeck, who has access to the latest submission material, finds the student’s midyear reports, which show that her grades appear to be on the upswing. All the officers relax, and some nod approvingly. This GPA rebound, coupled with her interesting extracurriculars and strong essay, satisfy them, and she is admitted.

Lisa Hill, who has 18 years’ experience at Goucher, has control of the spreadsheet. She highlights the student’s line in green. This discussion lasted a lean five minutes.

The next applicant is rated a 6C, meaning her academics are weak and her outside interests indicate she would have average impact on the school. Her essay is disorganized, her grades have declined, and she failed a core science class. They vote to deny. Her line is highlighted in red.

The next case is presented by Lederer, a recent graduate who majored in music and at 22 is the youngest of the officers. He is the only temporary member, hired through May to replace a staff member who departed unexpectedly. “This is an interesting case,” he muses. The student has a richly international background, is described as a “true thinker” in one recommendation and has solid SAT scores. Lederer is on the fence because the student’s grades are “a little strange,” ranging from 2.45 to 3.2 for an aggregate GPA of 2.59. Lederer notes, however, that his classes have been highly challenging. The officers think the student is intriguing — one even calls him “cool.” “He’s perfectly matched to Goucher,” Surbeck says, and the student’s line is highlighted in green.

Next: a girl who elicits a few groans with two D’s in 10th and 11th grades with a “non-specific” health issue cited as the reason. Surbeck decides they will wait-list her to “test her interest.” If Goucher was just a casual addition to her list of schools, they probably won’t hear back from her. If she wants to be kept on the wait list, that shows a degree of interest not evident in her application. At this point, she is a “ghost,” an applicant who has not visited or made any contact except through the application itself. Hill highlights her row in blue.

The committee can get through 60 to 150 applications per day. “We don’t want to set up a student for failure — that’s the wrong thing to do,” Surbeck says later. “I’m a believer that retention begins at the admissions stage.”

Goucher will accept 2,400 students, and 15 to 17 percent are expected to enroll. By contrast, an Ivy League school might accept less than 10 percent of an enormous pool of applicants, but 80 percent of those will enroll.

University of Virginia

At the public University of Virginia, where reading begins in November, the admissions committee is well into processing its 29,250 applications by mid-February. One-third of the applications arrive between Dec. 31 and Jan. 1, the deadline at many schools. Jeannine Lalonde,senior assistant dean of admissions, is reading at home partly because she is sick and partly because it is quieter.

Lalonde is also known as Dean J on Notes From Peabody: The UVA Admission Blog, where she discusses U-Va. admissions to help demystify the process. The reality is that the officers must deny most applicants, and it concerns her that during the wooing period, so many schools fill mailboxes with colorful brochures begging students to apply. She believes U-Va. doesn’t overdo it.

The path of an application through U-Va.’s admissions process is as complex as the variety of applications themselves. It is known to be selective:It accepts 27 percent of its undergraduate applicants, so most prospective students have done their research and fall within the parameters of the statistically accepted.

U-Va. maintains a holistic (incidentally, this word is extremely popular among admissions officers) approach to applicants. There is no hard cut-off for test scores that would single-handedly rule out an applicant. “Testing doesn’t drive decisions anymore,” Lalonde says. That said, a quick look at the statistics shows that the average SAT scores of U-Va.’s accepted students is a combined math and critical reading score of 1340; 92 percent have a 3.75 GPA or above; 93.1 percent ranked in the top tenth of their class.

U-Va.’s admissions staff consists of 15 deans, five counselors and roughly 10 temporary readers. The university is shifting toward a regional approach like Goucher’s, meaning officers will be in charge of geographic areas. This year the university is also increasing its targeted enrollment of first-year students from 3,360 to 3,485. (About 8,400 to 8,500 students will be accepted; 42 percent are projected to enroll.)

At least two people read each student’s file, more if the student has applied to a specific school at the university, or if he or she falls into the category of an underrepresented group. From January to March, deans and counselors each read 30 files a day.

As at Goucher, a student’s application goes before the admissions committee if more input is needed to reach a decision. “It’s like a puzzle; when you fixate on any piece, you’re missing something,” Lalonde says.

For those students who wonder if all their wordsmithing is worth the effort: “The essays are our favorite part,” she says.

Howard University

Linda Sanders-Hawkins was an undergraduate at Howard University, then a graduate student and then worked her way up to director of undergraduate admissions eight years ago. She wants to protect the standards and the legacy of this private historically black college.

She also sympathizes with the angst that students and their families undergo. She confesses that her own son, when it came time to apply to college, was doing the midnight deadline dance. She found herself sitting at the table with him, unable to believe that even she, a director of admissions, was in the same boat as so many parents.

This year, Howard received 11,000 applications; it will accept 54 percent, and generally about 25 percent of those enroll. Applications are divided alphabetically among eight admissions officers and as many as 20 faculty members who read applications to their particular schools or colleges of study.

In early March, a committee of two from the College of Engineering, Architecture and Computer Sciences (CEACS) meets. The college’s assistant dean for student affairs, LaWanda Peace, leads the discussion. Next to her is Harry Keeling, associate professor of systems and computer science. Ten files are up for review, each with a deficiency in either GPA or test scores. The committee looks at the documents, papers arranged in gray folders. A strong application (one with at least a combined 1080 in the math and reading sections of the SAT and a GPA of 3.0) might garner an outright acceptance, while a weaker application is discussed and ruled upon by majority vote.

Peace and Keeling examine one student’s transcripts to see if she took science and technology courses. She did — and in fact one of her letters is from her physics teacher. Her GPA is fine at 3.2, but her test scores were lower than the admissions officers like. They notice the encouraging letter from her assistant principal, who reveals additional insight: This student, through extraordinary determination, had lost an enormous amount of weight. The committee sees this as a sign of drive and character. Ultimately her honor roll status and her ranking in the top 30 percent of her class, along with the recommendations, gain her admission.

While Peace pores over an essay from a home-schooled student who lost her mother and had to make her way in a mainstream high school, Keeling does some calculations on another student whose high school uses an unusually tough grading system that lowered his GPA to a 2.7. There is a concentrated silence as every document is examined. Keeling is troubled by two folders in front of him: Neither applicant shows any real interest in technology. One student wants to go into music production, which isn’t relevant to CEACS. Keeling and Peace decide to redirect these two files to the College of Arts and Sciences.

Another student with an abysmal 2.1 GPA is a conundrum, but things become clearer as they study the file: This student had been the sole caretaker for an elderly grandparent, who then died, leaving the student on his own. Parents are not in evidence. His grades did take a turn for the worse but rebounded to almost 3.4 in his junior year, and he continued a rigorous curriculum with A’s and B’s in all the right classes. His high SAT scores and a top score on an AP exam persuades the committee. The members admit him — albeit with a recommendation he take the school’s summer bridge program.

Howard has recently begun to incorporate interviews into its admissions process, hoping to round out its understanding of a student whose qualities might not come across adequately in the application. “It helps us to participate more holistically to get to know an applicant,” Sanders-Hawkins says.

University of Maryland

The University of Maryland received 26,000 undergraduate applications this year. Twelve admissions counselors will each read more than 2,000 randomly assigned applications to fill 3,975 spaces.

At the moment, 10 counselors are seated in front of laptops around a large modular table. A basket of snacks rests in the middle. Projected on the screen is the file under discussion. Every document the student has sent has been scanned. U-Md. does not use the Common App, employing instead its own online forms. Admitted freshmen have a strong A-minus or B-plus average, with the middle 50 percent of SAT scores ranging from 1260 to 1410.

Colleen Newman, senior assistant director for freshman admissions, runs the meeting. The student under review is from out of state. She has a 3.9 GPA, but her SAT scores, at 990 combined reading and math, are low. They gaze at her transcript: A’s in ninth and 10th grades, and increased challenges in 11th and 12th bringing in A’s and B’s. The presenter says simply, “I really like her.” Her essays exude confidence, he says, and not only was the student on the honor roll for all of high school, but her letters of recommendation are stellar. She starred in several school musicals and is ranked 13th in a competitive class. “Let’s take the temperature of the room,” Newman says. “All in favor of fall admission?” Ten hands go up, and the student is admitted.

The next case is a boy with a 3.36 GPA and 1300 SAT. In this case, the test scores are fine, but the transcript is worrisome. The course load is not rigorous, and his grades are all over the place. There’s no telling how such a student might perform. He has not taken advantage of what his high school has to offer. The presenter thinks this student is not forthcoming in his essay. “Even his application feels very guarded to me,” she says sadly. Zero votes for fall admission, eight votes to deny, and two to offer spring admission.

“He’s got potential. I think a denial is very harsh for this type of student,” one argues. The presenter, who voted for spring admission, says: “I just want to give him a hug! I feel like, in the right community, he could do really well.” In the end, the majority rules. He will not be coming to U-Md. This denial took significantly longer than the earlier acceptance.

The last student of the day is an out-of-state boy with a GPA of 3.3 and SATs of 1209. His grades are chaotic, but his letters of recommendation are among the strongest the presenter has ever seen — one details the extreme kindness shown by the student toward a teacher who was going through hard times. Great essays, varied extracurriculars: The presenter is clearly taken with this young man. Another counselor is unimpressed: “I just don’t think he’s performing well.” Another defends him. “I like what people said about his character. He has high emotional intelligence.”

He is admitted by a clear majority.

Now we wait

So, in the end there were no headless chickens, no Ouija boards, no pin-the-tail games. Not at the schools I visited, at any rate. From the admissions counselors I spoke with and the committee meetings I witnessed, I felt a sense of humanity in their process, a pride in the hours (and hours) spent poring over applications. These officers seem dedicated to trying to understand the human student behind the electronic file. The process seems more like detective work than ax swinging.

And now it’s finally April, which means that most college-bound students have heard the news (good or bad) and received the envelopes (fat or thin). If you have been awaiting news, I hope you made at least one happy match.

How did my three boys do? Of the 18 schools they collectively applied to, they were accepted at 13 and wait-listed at four, so we are content. Now we have to see how on earth we are going to pay for three college tuitions. At once.

R.C. Barajas is a writer living in Virginia.

Saturday, December 5, 2020 at 11:54AM

Saturday, December 5, 2020 at 11:54AM